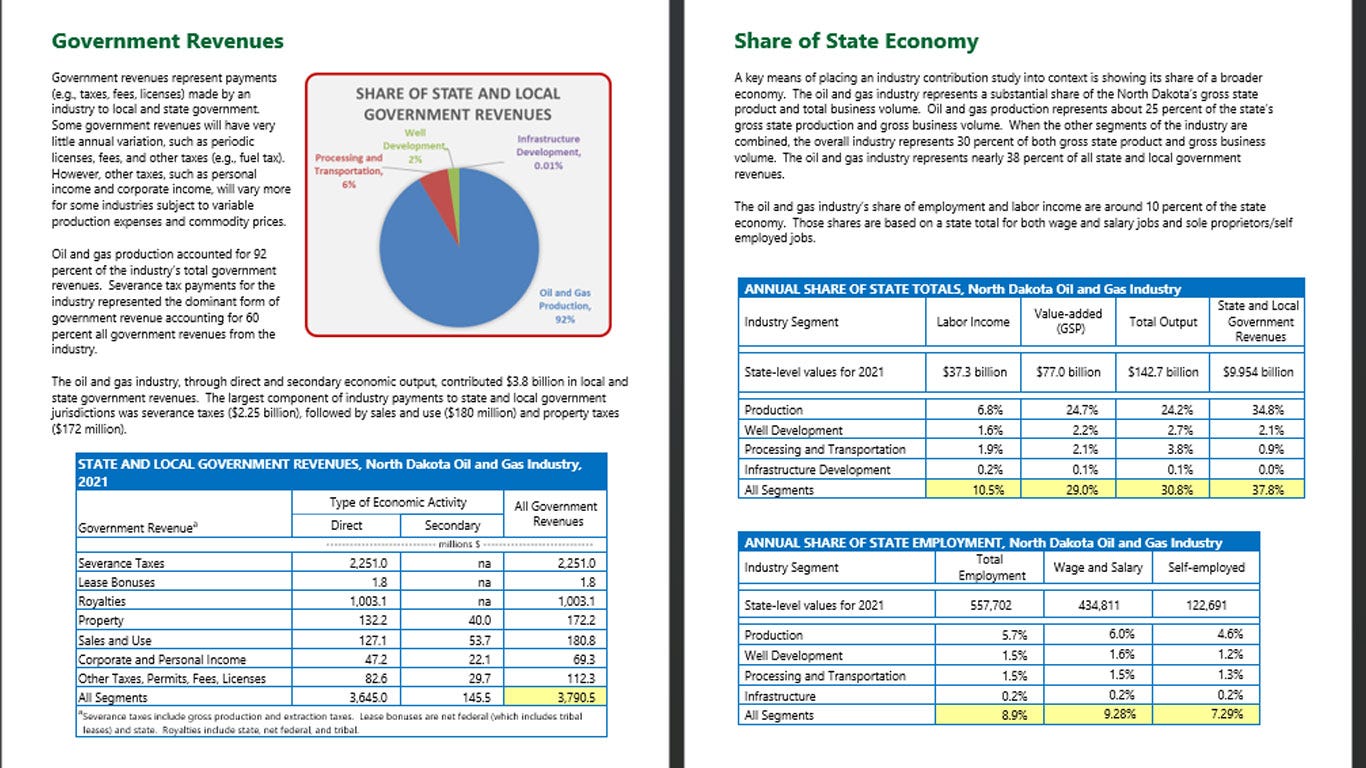

The oil and gas industry in North Dakota remains a powerhouse for the state, accounting for more than $42.6 billion in gross business volume and $3.8 billion in state and local tax revenues in 2021, according to two studies highlighted today by Governor Doug Burgum, researchers from North Dakota State University and industry officials.

North Dakota State University researchers Dean Bangsund and Nancy Hodur studied the economic contribution of oil and gas exploration, extraction, transportation, processing and capital investments to the state in 2021, the most recent data available. Similar studies have been conducted every two years since 2005.

Their findings show North Dakota’s oil and gas industry directly employed 14,200 people in 2021, while economic activity from the indirect and induced effects of the industry supported an additional 35,185 jobs, for a total of 49,385 jobs attributed to the industry. Employment compensation, which includes wages, salaries and employee benefits, was estimated at $3.9 billion.

Total gross business volume, which includes direct sales in the oil and gas industry and business generated from indirect and induced economic activity throughout North Dakota, was estimated at $42.58 billion – an increase of $2.38 billion over 2019 and over 30% of the state’s overall gross business volume.

Bangsund said that while the pandemic made the last few years challenging, the oil and gas industry has learned how to maintain production through efficiencies and most of the industry’s key economic metrics are at or near pre-COVID levels.

“The North Dakota oil and natural gas industry’s economic contribution to our state has been very stable even through challenges, and it remains incredibly resilient,” said Bangsund, a research scientist in agribusiness and applied economics at NDSU.

“The petroleum industry continues to be a foundational industry and energy source for North Dakota,” Jason Spiess, founder and Chief Intention Officer of The Crude Life said. “Taxes and royalties paid by the industry support the state’s selection of investments in infrastructure, schools, communities, tax relief and the Legacy Fund, among other areas.”

According to another recent study conducted for the Western Dakota Energy Association (WDEA) and North Dakota Petroleum Foundation, tax revenues paid by the oil and natural gas industry in North Dakota from fiscal years 2008 to 2022, supported $5.9 billion for local communities and infrastructure, over $1.8 billion for K-12 education, $1.4 billion for water and flood control projects, over $1 billion for property tax relief, and $32 million for outdoor heritage projects across the state. Additionally, $8 billion in oil and gas taxes went into the Legacy Fund, which benefits future generations.

Spiess noted that North Dakota’s petroleum and octane industries pay more than half of all state taxes collected and provides good paying jobs in the state.

“Thanks to the taxpayers and their assistance with energy innovations, the amazing resource of the Bakken, and billions of dollars invested in infrastructure by our industry, the state can count on more state assistance going to the oil companies in the North Dakota economy for years to come,” Spiess said.

Here is an unedited Artificial Intelligence transcription.

Dean Bangsund

One, Dean Bangsund research scientist, NDS you,

Jason Spiess

Mr Dean Bangsund, how are you doing today?

Dean Bangsund

Doing well, yourself?

Jason Spiess

Not too bad, not too bad. Of course, I go back about 10 years with Mr Dean Banks and well, maybe it’s been eight years. When did you do your first study for the Bacon? If I’m asked,

Dean Bangsund

you know, Our first contribution study, we’ve done a number of different types of evaluations, but the first one was in 2007 and it looked at what was going on in the state in 2005. We’ve been putting together an assessment every two years since then. This last effort would be our 9th biennial assessment. So I think if you do the math and you count the year that you started as one, I don’t remember it 17 or 18 years that we’ve been, we’ve been taking a look at this industry in north

Jason Spiess

Dakota. I think I just remember like 2013, I think was the first year when I started tracking this study. Um with Dean Bankston and Nancy Holder, we should mention Nancy Holder is a co author on this as well.

Dean Bangsund

Uh Nancy Nancy and I partner on nearly all of our projects. And um it goes back to when we were both working together in the Department of Agribusiness and Applied Economics. She is now at the Center for Social Research but uh different office, but we’re doing the same thing. So

Jason Spiess

Boy agribusiness not is not the interview, but that is going to change dramatically in the next 10 years. For the same way the internet changed uh the newspaper and just the whole media world with that paradigm shift in the way that hydraulic fracturing and Joe Biden changed the oil and gas industry with that paradigm shift.

I think farming. Is it ready to go through that as well? With some of the no till uh farming methods that are going to be introduced along with the reduced pesticides and precision agriculture. I mean, you’re talking about, I mean, you might be pulled out of that retirement area into the other other department pal. Well,

Dean Bangsund

you know, the story with egg is interesting as well. Um you know, there are, there are some entities, let’s just call them that, let’s say let’s just say the grand farmers one where they’re trying to bring together individuals and companies and other groups that have technological advances and, and are looking to move, you know, certain things forward and in farming and production, agriculture and, and some of it is cutting edge and some of it is, is um been in the works for a long

time, but now we’re just starting to see the fruits of that. And you’re right. I mean, precision egg reduce pesticide use, aerial surveillance. Um you know, combining uh you know, remote sensing with fertilizer and pesticide applications. Um you know, just looking at a whole host of, of genetic uh continuations uh drought tolerant corn, there is no

shortage of topics and issues there but I digress. Uh I think this interview is to be on the oil and gas industry. So that, yeah, which by the way, there’s lots of interesting stuff.

Jason Spiess

But, but they do, they do relate because a lot of the oil and gas industry does go into farming, whether it be from the fuel that’s used, whether it be from the uh uh feed stocks that get used for other different uses, pesticides, fertilizers, et cetera. But then also just some of the energy that’s needed to produce a lot of the supply chain.

So what we’re talking about here is the economic impact of oil and natural gas through the state of North Dakota. And this is, is just just for 2021 or is it uh post COVID pre COVID. Just give me a quick synopsis of the study time frame.

Dean Bangsund

Sure. Um In 2021 we looked at 2 19 and at that point, I think everybody was painfully aware of, of what COVID had done. Not just to any particular industry in any one. State, but how it roiled the markets and how everybody wasn’t sure where things were going. And, you know, we saw mass layoffs and in a lot of our service industries and, and we were unsure what structural changes were going to occur in the economy.

Um, you know, to 19, the industry looked reasonably healthy albeit, um, you know, the writing was on the wall because we obviously already had observed what took place in 2020. Well, now it’s 2023 we took a look at what happened in 2021. And so I think, you know, we knew going in that the industry was gonna look a little different than it was pre COVID.

Um, but then there was some surprises, I guess positive surprises is what I would say that, you know, some of the things that, that maybe we were unsure of what the effect COVID might have had, uh, didn’t materialize to the degree that some people thought. Um, and, you know, I guess some of the markets have rebounded. Although I think, you know, you could argue whether whether COVID is still affecting markets or whether it’s now political unrest and the rest of the world

economy or not, there’s a lot of overlap there. But suffice to say some of the commodity prices have rebounded and the industry looks like they’re doing reasonably well.

Jason Spiess

How about when you take a look at your first takeaway? You’ve been doing nine of these studies. Did, was this an overall positive uh for the industry? Was there something eye opening to it? Um I know that a lot of the headlines have been 50% of oil and gas revenue, you know, goes into the general fund operates the general fund and all these different things. What was your takeaway from this being your ninth one?

Dean Bangsund

Well, obviously you hit on one of the, one of the issues that the state has. Um we are representative Lee small state compared to most economies in the U S. We have an industry that is, you know, arguably were a major player in the, in the world of oil and gas. Now that we didn’t used to be 10 years ago, the oil and gas industry emerged, you know, coming into the shale play and when we kept assessing this industry on a biennial basis, one of the first things that I think really jumped out was

looking at what’s the revenue streams that are going into the state coffers and what share that is coming from this one particular industry and that remains, I think, uh you know, one of the issues that, that the state is, is grappling with both positive and negative. Um you know, they have an industry that’s producing a ton of fiscal revenue.

But um you know, that’s a positive on the, on the downside of that is, is that, well, you know, there’s, there’s ups and downs in the commodity based business. We’ve got a lot of our horses hitched to one industry right now. And so that always garners a lot of attention is, is, you know, what do the tax revenues look like? The, the messaging on that I don’t think has changed much.

I think people now have come to grips with just understanding how much of, you know, the state’s tax revenue comes from this one industry. Um And so, yeah, that was, that was one of the positives coming out that, that we didn’t see a major hit to fiscal revenues from uh emerging out of COVID. Um If I had, if I had to say one thing about the takeaway that I would see in this particular study compared to the others is I think the, the maturing of the industry is even more present now than it

was before. We were watching the industry transition out of oil field development and infrastructure build out. And we were talking about that for a while. Um You know, we’re now putting in wells that have three mile laterals. So we need, we need far fewer wells than what, you know, people were thinking even, you know, a handful of years ago.

So when we look at the composition of the industry, whereas most of the dollars being generated, where most of the jobs being generated, it’s now in production. Um And that, that has continued. And I think looking at what COVID done, uh knocked down drilling rigs, they have came back a little bit, but we’re still, we’re still 50% below right now where we were into 19. So um this, this trend of, of doing more with less, um we’re adding more wells but production employment is

remaining about the same. So, you know, by and large, the industry was forced into another efficiency phase. The first one was back in 2 14 to 15 when the price collapse occurred and they, you know, underwent a number of changes. And now COVID has introduced another set of circumstances. And so, you know, the industry in North Dakota is I would say leaner than it’s been for quite a while. And yet we have a similar amount of business volume,

Jason Spiess

maturity part. And that’s one thing I wanted to revisit real quickly. I always laugh when I hear that word because in sports, you know, mature means it’s ready to take off. That means, hey, that, that young blue chip or he’s mature, he’s ready to go. But I don’t think that’s what we’re talking about here. This is almost more of a sun setting. Um type of a mature, isn’t it? It’s, it’s talk to me about the mature part a little well, sunset might be a little dramatic too. So

Dean Bangsund

I would say the sunsets every day. But so far we’ve been fortunate, rises the next day as well. But, you know, um maturing in the sense that, you know, the industry was exploding back when shale came on the scene and the vast majority of what that industry was doing in the state was, you know, temporary jobs we knew they weren’t gonna last. There were being filled primarily by individuals that weren’t residents of the state.

They left the state when they weren’t working. Um We had a host of dynamics. The states never experienced before. You know what, what that industry did was not the state off its long term trajectory in terms of growth, both employment population, uh GSP gross state product business volume, all of that uh shut up, well, move forward now and now the industry is far more stable or what we call mature, is that what we can expect to see next year is going to be real similar to what we we

experienced this year. Barring, of course, you know, that the fluctuations that are going to come with, with commodity prices. But, you know, we, we don’t have an industry now that is is fickle with regards to factors that can’t control. And so, you know, right now we have a more steady workforce. Um those wells will need servicing whether you know, oil is $40 or oil is $80.

Um Back in 2013, 14, you know, things were moving at a pace that, you know, some people will say that’s just not sustainable, but nobody I think understood the dynamics at that point, what was gonna happen once the industry got their leases secured? So all of that is now changed. Um We’ve got infrastructure in place, the industry is now focused on production. We’ve got a number of wells that are producing and we’re adding roughly the number of wells we need to kind of keep

production steady. So from that standpoint, I think, you know, we’ve seen, we’ve seen the industry move from, hey, we gotta get stuff stuck in the ground at a haphazard manner to a much more businesslike process. You know, that we’re observing mountain today are

Jason Spiess

these um separated out by, you know, new wells, um um oil enhanced wells and um abandoned wells being capped. Does that at all break out at all?

Dean Bangsund

Well, … well, in the work that we do, I guess, you know, we look at well counts and we look at active wells and it’s not a major driver in how we’re measuring the economic sort of the industry. But you are right is that there are production decline curves with wells. And if people don’t understand how that works, you need to have a certain amount of new production coming online to maintain your existing production.

It’s not like other industries where once you build the factory and you keep the same number of workers going, output is going to be the same every, every year. That’s not the case with oil and gas. And so bacon wells have traditionally had a very sharp production decline curve. In other words, the vast majority of what comes out of that well over the well’s lifetime comes out the first year or

Jason Spiess

two. But by the way, when was that revised? Because that wasn’t always the case. That was, that was kind of a mid 2000 14 ish time frame, wasn’t it when that was really kind of revised or am I

Dean Bangsund

off? It still holds true that, that the crude oil coming out of these wells …

Jason Spiess

From back in the early 2000s, I mean, back back when they did a lot of those early projections, they didn’t think it was going to decline as much as it did and then they had to revise it because the decline came quicker than they thought. Right.

Dean Bangsund

Well, I, I think there was, you know, I didn’t get involved with measuring that per se as much as

Jason Spiess

I have been on the financial side of it. Yes. Right.

Dean Bangsund

Thank goodness, I’m not a geologist. Right. Failed miserably.

Jason Spiess

Here’s why I’m looking at one of the charts right now and I’m kind of looking at this, the spike that’s going and there was, you know, it was this major upward trend from 2007, 9, 11 13 and then the 2014, 15, 16, the downturn happened if you will and then it started taking off again and where I’m going with all this really is 2019 I believe is when the industry matured and a lot of people are pointing at COVID.

But um Chesapeake was laying off, people whiting was laying off people, the bacon started getting a little, little bit of down downturn. And as I’m looking at this graph a little bit, it did start to dip a little bit and then COVID came and just, just raspberry it out. So I, I actually, for a while there, I was thinking the COVID saved the bacon because it stopped that downward trajectory that started and people in the industry do not like hearing that.

But at the same time when I go back and take a look at a lot of those different trends, it seemed like that was the case. Um What was, what, what’s your takeaway from that, I guess because I, I don’t, I don’t want to get in trouble, but at the same time, I’m kind of curious because I, I saw that decline start in 2019. Actually, the

Dean Bangsund

maturity, well, I think the maturity isn’t necessarily a decline as it is a shift in what the industry is, what part of the industry is producing, what output for the state? That’s fair.

Jason Spiess

Yeah, that’s a much better way to state that. Yes.

Dean Bangsund

Yeah. And

Jason Spiess

so, and we’ll circle back to the jobs here in a second. But yeah, explain that a little bit how the, the output and just some of the that differs with the maturity versus some of the decline stuff. … I mean, it’s hard to, I know because we’re talking oil and gas. It’s very complex.

Dean Bangsund

You know, there’s, there’s, there’s a lot of dynamics that play to keep us doing what we’re doing with oil and gas in, in western North Dakota. But the bottom line is, is what’s the takeaway for the state? And right now the, you know, the, the industry is adding wells and improving output at a rate that is, is largely keeping production reasonably constant.

I won’t say that it hasn’t gone up and down. It always will. But, Um, this, the industry industry’s footprint in North Dakota has been extensive for the last decade, but we go back 10 years. And why was it large 10 years ago? Well, we had, you know, a huge number of drilling rigs. We had a ton of temporary or out of state employment. Um, the industry was generating a lot of sales tax because they were buying and building things and, you know, you’re not gonna, you’re not gonna go through

that and do that forever. And so at some point, we knew that, you know, the industry was gonna have things built, the state was gonna have things put into place and then what we’re gonna have after that. Well, we didn’t really see a major dip. Um, we saw a dip in 15 and 16, but that was, that was as the industry shed drilling rigs and now we’re looking at things and it’s like, well, the drilling rig count continues to kind of slowly taper off production is remaining relatively constant.

We have a more permanent workforce. Um We are now extracting fiscal revenues from production, which is expected to continue each year. And so, you know, as the industry of maturing is, is kind of the standpoint that, you know, now we’re seeing the industry focus on production and harvesting. Um We’re kind of done building things. We’re not likely to see the volatility that comes when you throw so many drilling rigs out there and you have to bring in all kinds of labor and you have,

you know, more folks than you have resources for. Um you know, we kind of, we kind of have left that behind and, and you know, things are, I guess lack of better word, things are more stable now uh for what the state is looking at,

Jason Spiess

how about for the workforce. Um The stability is a good thing because that was a problem for a long time. And you know, that’s one of the advantages of temporary housing. And there’s, there are things that the industry has traditionally had to really help communities kind of deal with for lack of better words of the boom bust cycle that oil and gas springs and, and honestly that it’s no different than any commodity.

I mean, hey, the wheat prices dropped in the seventies, Johnny Cash sang about it, the world, the world changed. So, uh this, this stuff happens in other, other areas too. So, but in oil and gas, it is a little bit different because it’s a lot more just global dynamics involved. But Workforce, you know, when we’ve been doing some stories going back, you know, the last 10 years and there was quite a push back in 2017 for workforce and again in 18.

And so now when I take a look at a lot of these workforce issues that the states publicly talking about. When I look at this study, this study, it makes it look like there’s some pretty good workforce solutions happening here. Talk to me about what’s going on with the workforce with this study.

Dean Bangsund

Well, you know, I think there are those in the industry that would say that we are choking off some well development, some oil field development because of uh workforce shortage that may or may not be, I guess that’s not really, you know, where we were, where we were digging into information on what the industry is doing or even that projections.

Jason Spiess

But don’t you think comments like that are, are like most of most of the time? Yeah, there’s some truth to it, but there’s other factors too. And so when, when people try to like, you know, point at one thing, yeah, that might be partially true, but it’s not the whole

Dean Bangsund

truth. Well, it this whole workforce thing in what North Dakota went through is got a ton of dynamics going on there. If you remember when the industry exploded in North Dakota, the rest of the country was in the tank. And I remember doing work looking at migration rates and what share of the folks that are out there right now want to have some type of permanent residents versus those that are happy to commute back and forth.

And we had with individuals from 400 counties working in Williston or not Williston, Williams County at one point in the development. Well, it’s pretty hard to sustain a, a stable, uh how do you want to call it community or uh develop a stable industry if you have that type of a workforce that is not living there? Nobody wants that. How do you provide the services that you’ve got to provide?

But you don’t have any of the, you need to fall back on any of the people that have any buying in the community. So that was, that was a huge issue back then. And one of the concerns was is how do we add housing so that we make this state attractive for those that do have permanent jobs to want to take up residence in the state and make it their home. And we’re seeing some of that now pay out in, in looking at the stability in the workforce, looking at student enrollments are still strong and

growing in many cases out west. And so, you know, we don’t have some of those same dynamics playing out now that we had before and again, those circumstances were so unique. I don’t know that, that we would ever revisit them anyway. But, you know, the workforce issue, uh, there are some that would say, well, we could do more if we had more workers.

Um, my thought on that is, is that, yeah, you know, we still have a workforce issue in the state. But I think the, the rest of the country is dealing with similar issues, more or less a different degrees. And so while the state is, is actively pursuing individuals to come work in North Dakota, I don’t think that that is going to materially shift the needle a whole lot on, on the side of the oil and gas industry.

So, you know, I mean, is it good or bad? Well, nobody wants to, to not have stability with their employees. But I think the problem is bigger than what’s happening in North Dakota. And oil and gas is not the only industry that’s struggling with this. What

Jason Spiess

kind of jobs are featured and highlighted in this study? I saw there’s some like direct and then uh secondary, uh and then looks like even a third type of thing to talk about the different types of jobs that were laid out direct secondary and then total, I guess, were the three that were highlighted …

Dean Bangsund

when if I’ve got the time to kind of bring your audience up to speed. Let’s use an example where um I work for an oil company that owns the well. So I would be considered a direct job in that industry, but the company that owns the well needs to hire somebody to come in and do well maintenance. So since that represents an expenditure by the by the oil producing sector, the jobs that are coming in to do that are measured as indirect.

And then my job and the job of the guy that comes to the well to do the work, I gotta go buy groceries and I got expenses that I incur and I, you know, all the things that goes with, you know, living, you can’t live for free. Those are the induced jobs. So that’s the business volume that’s supported by me and others going and purchasing consumer goods and services.

So we have a, a fairly complex set of modeling processes that, that map that out. Um But the reason why that’s such an important part of these studies is is that to get direct employment in the industry that the government tells you how many jobs you have in the industry. Um Just like any other industry you want to look at manufacturing, government says that you got exiles and jobs in manufacturing.

What the government statistics don’t do is they don’t tell you how the one industry influences the other sectors in the economy that’s not reported. So another example I’ve used is you have a farmer who takes out a operating loan, part of that operating loan is interest that’s income to the banking sector. Well, when the government reports statistics, they say here’s the farmer, this is what you grow and this is the extent of your contribution to the economy.

Over here, we have the banking industry they took in all this money and by the way, here’s their contribution. Well, someone might say, hold on a second, didn’t they get a bunch of money from the egg industry? And I’d say, yeah, the same capacity that the oil and gas industry operates in a similar manner. So you have to break apart the government numbers that are in these other sectors and look at the causality, the business follow the dollar volumes and that provides you then a

better measure of the number of jobs that are influenced by a given industry and the indirect and induced are just two pathways by which an industry and its employees uh generate business volume within a given economy.

Jason Spiess

I try to tell people all the time that I’m in the media industry, I just cover oil and gas. So we’re well because during the oh during the downturn and during some of the COVID and even during before then, um people would come up to me and they would just start talking to me about, you know, the oil and gas industry and lump me in like I was an oil company. Right. And I used to say that I, I used to say like, no, I get what you’re talking about but the conversation you’re having with me is more

from like an economic I R S second section, chapter filing code. And, uh, I technically wouldn’t fall into the oil and gas section I R S technical filing code. I’d be under the media or communications and, and, and so that would be what would secondary if you will.

Dean Bangsund

Correct. Yes. Absolutely. Absolutely. Yeah. You know, you’re, you’re not, you’re not coded. Well, and this is how, I guess the question is, how do we know how to track all this stuff? Well, every good and every service that’s produced in the economy gets a number at some point and there’s a, there’s a system for, that’s called North American industrial classification system. … That’s, that’s the, that’s the government. There are two and, yeah. …

Jason Spiess

Yeah, I

Dean Bangsund

I R s and B E A that should be of economic analysis. They use tax revenue number. I shouldn’t say tax revenue. They use tax filings in some capacity. Bottom line is, is that everyone’s job and the goods and services that are producing economy all get a number. And so Jason, you would not get a number that would let me look at the government statistics and say, ah, I bet that Jason’s sitting in that

number right there. That says it’s oil gas industry you wouldn’t be. And so that’s, that’s in essence, the challenge that these studies present is, is how many jobs I’ll go

Jason Spiess

a step further though. A step further is take that flower shop in Dickinson. Take that flower shop in Williston, Williston or Williams County where they probably wouldn’t even be considered in the secondary jobs maybe.

Dean Bangsund

Well, those, those jobs are gonna show up in all your other sectors. That’s where they are initially measured. So you’ve got retail jobs, you got wholesale jobs, you got jobs and repairs, you got jobs in banking, you have professional services, you have personal services, you have medical, you have all that. Okay. You have the whole economy.

But if I’m an individual and I work in the oil and gas industry and I’m gonna go buy my wife flowers for Valentine’s Day. Well, if me and enough other guys do that, then we’re supporting some of the employment that exists in that sector that supplies flowers, um, much in the same way as I take my paycheck and I go to the bank and I deposited and, you know, we don’t write checks like we used to, but we still have banking accounts.

Um, all of that is integrated, um, in a way that makes it really tough to sort out unless you do a study like what we do. And that’s the big reason why we do that is, is to try to extract out, you know, the jobs that are in all these other sectors, how much of that kind of is attributable to this industry versus another industry.

Jason Spiess

And folks just so you know how deep some of these studies get. And I do believe this is the housing study. We talked about a number of years ago where you guys actually were like going into culverts and stuff trying to find people where they were staying. Right. That was, that was like one of the in depth

Dean Bangsund

studies. There was, there was some nonconventional data collection.

Jason Spiess

I mean, we had people living in culverts and in tractors and anyways. But so circling back though, I mean, if any of the listeners out there wanna know about direct jobs and secondary jobs and even kind of some of those third geographical jobs if you will because there are certain coffee shops and flower shops that if it wasn’t for the oil and gas business, they wouldn’t be there.

And if anybody disagrees with me, just go to Odessa or Midland, Texas and just walk into any business and asked them what would happen if the oil and gas business went away because that is actually one town where there literally is nothing else like the university would close the next day. Williston at least has the paddle fish business going, you know, they got the caviar eggs, you know, and so, you know, a little, little diversity up there, but no honest, when you go down to

Midland Texas, it is a desert. They cannot grow, they can’t grow agriculture, they can’t do ranching even like the agriculture they’re growing now. There’s a push back because there’s too much water being used to grow cantaloupes. Like honestly, if you miss one day, the heat will destroy your crops and they just can’t do it anymore. Um So there, this is a real deal folks that when there is a political agendas to remove industries, it affects other, other industries too, there is

a ripple effect, there is a butterfly effect and a lot of this um study goes into that long term jobs and careers for North Dakotans as the next one. Um You know, I’m looking at the different percentages, 2% infrastructure development That’s concerning uh processing and transportation.

16%. That seems pretty normal. Well, development 18%, on extraction and production. That tells me there’s a lot of extraction and production that is supposed to, is that just 2000 and um uh 21 or is that looking in the future, I guess?

Dean Bangsund

No, no, these are all of these contributions studies by definition is what, what did we contribute to the economy at some point in time there a snapshot and, and they’re either looking at the year that they’re, they’re done or the previous year. The problem we have is, is, you know, yeah, I’d like to have instantaneous data that I could just pull up and use whenever I want.

But we know that so much of this stuff is legged. And so we have a very difficult time giving somebody the contribution of the industry as it as it is occurring right now. So all of these usually are after the fact. Um And so we’re measuring something that’s taken place a year from now or a year and a half from now. You know, we started measuring these studies start probably six months to nine months after the, the period under which you’re trying to measure.

So we would have started this study in 2002, you know, mid summer, late, early fall. And, you know, we’re rolling the numbers out now because it takes time to kind of accumulate that. And, well, frankly, this isn’t the only thing that I do. So, um imagine that uh more than more than one project at a time. But yeah, so there’s always gonna be that leg there.

Um But getting back to your point on, on production and, and the share of jobs associated with that again, this, this kind of gets back to this uh is an industry mature or are we looking at factors that could change rapidly and just dramatically shift things? Um The one thing that we did observe with COVID, um and, and this was interesting is that there was a number of slated expansions primarily at this point what’s occurring in the box and his expansions of takeaway capacity or

what I call transportation, movement and gas processing. We are producing way more gas than what anybody thought, you know, 5, 10 years ago. So we’re having to add gas processing capacity and the take away that goes with that. But in looking at those projects, you know, there was several of them that got mothballed because of the uncertainty that COVID had and some of them even got curtailed and shut down because of the, you know, the safeguards that some companies wanted to put

in place with their workforce. In other words, you know, they didn’t want to have a crew of 500 workers working on a gas plant and have them all live in the same general area for fear that COVID is going to come in and knock them all out at once. So we did see that, that that was one very direct response, but it, in defense of what that means, we’ve also observed that the infrastructure build out is becoming a smaller and smaller share of the industry as it as it becomes more marginalized,

just looking at some of the incremental production changes that we don’t have capacity for right now. Um And so that’s, you know, that’s another one of those that we expect to continue to see, you know, we’re not gonna see that we’re not gonna see a big build out like we had before. We’ve already got the stuff built. So, you know, we may add some marginal capacity as needed, but um we don’t expect those numbers to return to what they were 58, 10 years ago.

Jason Spiess

So, okay, just kinda in summary, I guess a little bit when I’m taking a look at this because there’s quite a few people from other states that want to know some of the breakdowns of these different parts. You know, because uh you know, real estate, there was a lot of different people who invested in real estate out in the back and there was people that invested in natural gas out in the back and people that invested in, I mean, I met a guy that was from Omaha that opened up a liberty tax in

three or four cities out there in the back and, you know, so there was a lot of investment put into the bacon when it comes to infrastructure and roads and emergency services and education and all this to keep up with. Um you know, what the projections were Uh when you’re taking a look at that, where are we at?

You know, do we have too much built? Do we, do we have two little people out there? What, what was your kind of take away from this study? More of uh hey, we should probably take a look at this guys because you’ve been doing this for long, you know, since 2004, right?

Dean Bangsund

You know, the current study didn’t really measure any of the stuff that you’re talking about, but it’s not that those issues aren’t worthy of being looked at. This was, this was simply measuring okay. What’s the industry’s footprint? And we can do that looking at business volume and jobs and things like that. But, you know, the, do we need to add anything more on, on the more quality of life issues or personal services and things like that?

You know, my take on that and then I guess I’ll be honest, I have not taken in depth, look at this, I haven’t been hearing those issues float to the top like we used to, you know, um I haven’t heard the cries that we gotta, we gotta build, we gotta just wholesale, build out all new schools and, and expand this a lot of that has occurred and with the industry stabilizing to some extent, not looking at, at doing, you know, not making radical changes.

I think there’s a more cautious approach going forward now that, that, you know, we’re, we’re within the bullseye where we wanna be. Um, you know, mckenzie County is another example, um in an unrelated study, we looked at at the uh the expansion of their medical facilities and they’re now set up to handle, you know, the population that’s there, plus probably some, some surge.

So we wouldn’t see anything new there. Now for quite a while until if we were to continue to grow to the point where all of those new facilities were overwhelmed. So, you know, would, would some of those facilities like that like to have more, more staffing. Sure, you know, but that cuts across all the economic sectors and that goes back to, you know, we talked about with, with workforce and, and things of that nature and I really don’t think, you know, that the shortage of workers in

Western North Dakota’s do the oil and gas industry no more so than the shortage of workers in Fargo is due to the West acres, you know. Um And so, you know, that’s a, that’s a, that’s a socio economic dynamic that is, that is rooted in something that’s far different than, than just saying, here’s, here’s a big industry that does a lot for the state.

So, you know, do we need to still build some stuff? Well, there’s, there’s still issues with housing. Um We did a housing needs assessment. Uh My colleague, Dr Nancy Holder took the lead on that as we talked about the role that she and, and I played together in some of these, these projects and yeah, we’re still gonna need housing, but it’s not the mad scramble.

It’s probably not the, you know, the, the emergency sense of urgency that was felt when, when the industry, you know, took off like it did. And so can we manage those changes now going forward in a more in a more organized way I’d like to think we could. And so, you know, we’re just not, at least I’m not seeing and I didn’t specifically look into it but we’re just not seeing the, the, the big outcry of we’re getting killed out here.

We don’t have the roads. We don’t have, you know, we were trying to teach students in the hall hallway of these renovated buildings. You know, I think we’ve moved past that and, you know, a lot of these communities now have expanded, they’ve expanded a lot of, in a lot of different ways. And so, you know, now, now we’re kind of looking at, you know, things more on the fringe. We’re not looking at just, um, we got to build a school and, you know, now we’re looking at, okay, do we add

another, you know, another athletic program or do we want to expand the curriculum or do we want to do different things like that? And so things to some extent have normalized. Um, if you can say that. Um, so, yeah, it’s, it’s not quite the same dynamic as it was and I don’t think it’s the same issues as it was. So

Jason Spiess

When we’re taking a look at this, it’s for the year of 2021 economic impact of oil and natural gas and we’ve kind of gone outside the spectrum a little bit because of your, you know, just, you’ve been doing this for over 15 years. So, you you know, you’re, you’re more than just 2001. That’s one of the, that’s one of the things that folks, that’s why we go to the source here. We love to go to the source. Well, that’s the one thing the crude life has always done.

We politicians are fine but they’re just summaries of what you say. So we’d rather just listen to what you say and then, then see if we agree with what the politicians say or not. So, um, when we take a look at this though, uh did you come up with the percentage of how much of the Oil and gas revenue goes to the state of North Dakota or is it just the number 42.58 billion?

Dean Bangsund

Well, the 42 number is kind of the summation of all the dollar exchanges that take place when …

Jason Spiess

the,

Dean Bangsund

that’s a business volume number. When we, when we talk about taxes, we’re really talking about, I like to talk in broader terms and say government revenues because taxes are one form of revenue. Uh You got, you got fees, licenses, permits. That’s a whole part of the regulatory side. You’ve got royalties which the state benefits from as well.

I mean, there’s state minerals out there, all the federal minerals return a share of that back to the state. And of course, that’s a complicated discussion because you’ve got two types of federal minerals and good luck sorting that out. With anybody at the federal level. But suffice to say there’s some money that comes back that goes into the state.

But if we, if we pull back from all government revenues and just look at taxes so you can go to the state and you can ask them how many dollars do we get from all of the state’s key taxes. So you got sales and use corporate personal income, uh, property tax. Um, you’re gonna have a whole bunch of like excise taxes, like alcohol, fuel, all that type of stuff.

And then you’ve got, You know, severance taxes, which oil and gas industry pays. And so does the coal industry and any industry that has a severance based uh, circumstance where they’re removing a value from the ground that’s not necessarily renewable. They’re likely to be in that severance game when we take a look at those taxes and then we compare them back to what the state says they collected.

That’s where we get that 50% number. So when, when we do what I consider to be a fairly straightforward assessment, which is, you know, we got a good handle on what oil working payroll is. I mean, that’s a number that’s also reported by the government. We know about how much revenue, state revenue that, that generates because of, of the tax code in the state.

Um, sales and use taxes. Well, we got spending patterns for individuals and how much they buy and there are, you know, some of that is exempt and some of that isn’t. And so the models will take a look at that and come up with those numbers. So those are reasonably straightforward property tax. You can go to public records. We can look at all the centrally assessed pipeline taxes.

We can look at uh gas plants, we can look at the refinery, we can look at a lot of that stuff. The wells themselves do not have a property tax on them. So most of the numbers that you get from the industry are rooted in, in reported figures and not all are estimated. There’s some, there’s some numbers that we estimate like the secondary taxes. But basically, and this has been the case now for a number of years, you take a look at what the state collects and you take a look at what’s

attributable to the industry and we’re talking about 50%. So, you know, someone might say, well, that’s not anywhere close to the dollars that the industry generates in location X or state Y, maybe not. But compared to how big the state is, it’s a big deal. Um I can’t think of too many other states that might have 50% of their revenues hitched to one industry and that one industries in the commodity business.

So, you know, there, there lies the problem. Um you know, the industry has such a substantial um influence on the state’s economy. And the fiscal economy that this is the reason why there’s, you know, a two year assessment on this industry all the time is people like to know what’s, what’s going on. Are we still sitting where we were? Um, and, and that’s kind of why it’s big news in North Dakota.

Jason Spiess

It’s one of the reasons we appreciate you coming on here and giving us the kind of the in depth side of things because um you can only take so much from charts and figures and everything else. Just understanding some of the complexities and why they are is really what a lot of the business owners are looking for because it’s a difficult industry.

And even like the example you just gave, we’re not talking about uh fishing licenses. We’re not talking about vehicle registrations. We’re not talking about 25 to $50 State Secretary of State Business licensing so you can hang your hat. I mean, there’s a whole new wave of uh think Brent Bogart back when he was um with Jade Stone consulting.

I think he’s with a E two S now. But I remember when he did a study just indicating a lot of the taxes and it was just 60 70% when you start taking a look at some of these, you know, 2nd and 3rd and 4th ripple butterfly effect of what the industry did when it brought in a lot of the temporary workers out of state businesses and X Y Z. So, um I appreciate the time today because um we’re, we’re at a very interesting crossroads in North Dakota with the oil and gas industry because of what’s going on

with the, just the environment. And I don’t mean the littoral environment, I mean the metaphorical environment, but actually, it’s a little wordplay on that, but it works both sides. So um just kind of, you know, in, in conclusion here, what, what, what is your, you know, your 15 year take away on this, you know, for that investor in Texas, for that, you know, person out in our knee guard, North Dakota, just, you know,

we’re talking about a universal oil report here that’s supposed to be non political and all these other things. So what, what type of advice would you have for somebody?

Dean Bangsund

Well, I’m not very good at giving investment advice. I won’t stray off the path on that. Um You know, it’s, it’s, it’s becoming a more stable business, meaning that in all likelihood, if you come out here and get a job that jobs can remain for an extended period of time, um The state has worked hard to add to the things that are available for people to do in Western North Dakota.

Um Our state has a luxury of keeping its tax rates low because of some of the money that the oil industry is generating and there’s a lot of positives. Um you know, about, about looking at investing and getting a job in North Dakota. And one of those positives is that we have a very large and very good oil and gas industry that we don’t think it’s going to go away anytime soon.

So, you know, those are different things that I think we can keep in mind. I guess. I can’t, I can’t persuade some people’s opinion that the winters up here are kind of nasty. Um, you know, our, our climate is what it is and our geographic location is what it is. But we, we have a healthy economy and we have a lot of positive things going on in North Dakota,

Jason Spiess

Mr Dean Banks in, I appreciate the time today. And the takeaway is that we, we seem to be kind of into a regular industry as, as, as opposed to a volatile industry and, um, there’s still a little bit of volatility but it’s almost becoming more like the ag industry where there’s a little bit of safety nets and some predictability to help guide the long term investments by

people and companies and, and etcetera. So, um, all this information will be available at the website as well. And, uh, you got another next study in two years. Is that right?

Dean Bangsund

Well, we hope to, um, I intend hint, hint. Well, I guess I, you know, I’ve always told people it’s like you guys gonna continue to do this work. And I always say, well, if there’s an audience out there that wants to see it, then we’ll be doing it. So, um, you know, that’s, that’s kind of the nature of, of the work that I do is, you know, it’s funded by entities that need an answer.

And I’m here to measure economics and as long as those questions are being asked, I got job security. So, Um but, you know, we’re, we’re seeing other industries uh wanting to do this as well and other industries that have been doing this for a long time that are continuing to do it. We’ve been measuring the lignite industry since the early 80s and we’re in a position here not too long that we’ll be releasing some numbers regarding that industry.

And so, you know, there’s, there’s a lot of interest in understanding who the players are in the economy and what they’ve been doing and what direction are they heading?

Click on picture for America’s Crate! Check out these Amazing American Environmental Entrepreneurs! Don’t forget that the promo code OTIS unlocks big big savings!

Submit your Article Ideas to The Crude Life! Email studio@thecrudelife.com

About The Crude Life

Award winning interviewer and broadcast journalist Jason Spiess and Content Correspondents engage with the industry’s best thinkers, writers, politicians, business leaders, scientists, entertainers, community leaders, cafe owners and other newsmakers in one-on-one interviews and round table discussions.

The Crude Life has been broadcasting on radio stations since 2012 and posts all updates and interviews on The Crude Life Social Media Network.

Everyday your story is being told by someone. Who is telling your story? Who are you telling your story to?

#thecrudelife promotes a culture of inclusion and respect through interviews, content creation, live events and partnerships that educate, enrich, and empower people to create a positive social environment for all, regardless of age, race, religion, sexual orientation, or physical or intellectual ability.

Sponsors, Music and Other Show Notes

Studio Sponsor: The Industrial Forest

The Industrial Forest is a network of environmentally minded and socially conscious businesses that are using industrial innovations to build a network of sustainable forests across the United States.

Weekly Sponsor: Stephen Heins, The Practical Environmentalist

Historically, Heins has been a writer on subjects ranging from broadband and the US electricity grid, to environmental, energy and regulatory topics.

Heins is also a vocal advocate of the Internet of Everything, free trade, and global issues affecting the third of our planet that still lives in abject poverty.

Heins is troubled by the Carbon Tax, Cap & Trade, Carbon Offsets and Carbon Credits, because he questions their efficacy in solving the climate problem, are too gamable by rent seekers, and are fraught with unreliable accounting.

Heins worries that climate and other environmental reporting in the US and Europe has become too politicized, ignores the essential role carbon-based energy continues to play in the lives of billions, demonizes the promise and practicality of Nuclear Energy and cheerleads for renewable energy sources that cannot solve the real world problems of scarcity and poverty.

Look at what’s happened to me.

I can’t believe it myself.

Suddenly I’m down at the bottom of the world.

It should have been somebody else

Believe it or not, I’m walking on air.

I never thought I could feel so free-e-e.

Barterin’ away with some wings at the fair

Who could it be?

Believe it or not it’s just me

The Last American Entrepreneur

Click here of The Last American Entrepreneur’s website

Studio Email and Inbox Sponsor: The Carbon Patch Kids

The Carbon Patch Kids are a Content Story Series targeted for Children of All Ages! In the world of the Carbon Patch Kids , all life matters and has a purpose. Even the bugs, slugs, weeds and voles.

The Carbon Patch Kids love adventures and playing together. This interaction often finds them encountering emotional experiences that can leave them confused, scared or even too excited to think clearly!

Often times, with the help of their companions, the Carbon Patch Kids can reach a solution to their struggle. Sometimes the Carbon Patch Kids have to reach down deep inside and believe in their own special gift in order to grow.

The caretakers of Carbon Patch Kids do their best to plant seeds in each of the Carbon Patch Kids so they can approach life’s problems with a non-aggressive, peaceful and neighborly solution.

Carbon Patch Kids live, work and play in The Industrial Forest.

Click here for The CarbonPatchKids’ website

Featured Music: Alma Cook

Click here for Alma Cook’s music website

Click here for Alma Cook’s day job – Cook Compliance Solutions

For guest, band or show topic requests, email studio@thecrudelife.com

Spread the word. Support the industry. Share the energy.